Coaching Trends

The pandemic underscored the value of coaches in the lives of children to benefit their social, emotional and mental health. Coaches need to create a space where children feel safe and a sense of belonging – which isn’t always a given in sports. The trends below come from the Aspen Institute’s State of Play 2022 report, courtesy of data collected or analyzed by the Project Play team or articles and research produced by other entities.

Top 5 Coaching Trends

1

Coaches need and want more help addressing the mental health of players. Almost all coaches said they feel strongly about their ability to coach X’s and O’s, foster a positive environment, and promote good sportspersonship. However, there was less confidence to deal with the mental aspects of sports. That was a key takeaway from the National Coach Survey, a first-of-its-kind analysis of coaching behaviors, experiences and needs in the United States. Conducted in partnership between The Ohio State University LiFEsports Initiative, the Aspen Institute, Susan Crown Exchange and Nike, the study surveyed more than 10,000 coaches from every state and in various sports and settings.

Only 18% in the National Coach Survey reported feeling highly confident in their ability to link athletes to mental health resources. This was coaches’ second least-confident behavior behind helping athletes navigate social media pressures. Very few coaches felt confident in identifying off-field stressors for athletes (19%) and referring athletes to support (18%). Beyond sports skills and strategy, coaches expressed interest in more training on relationship building (70%), performance anxiety (70%), motivational techniques (70%), leadership development (69%), team dynamics (67%) and mental health (67%).

In the latest mental health study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, youth who felt connected to adults and peers at school were significantly less likely than those who did not to report persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness. Youth who felt connected were twice less likely to have attempted suicide. Coaches can’t immediately become trained evaluators of mental health symptoms. Instead, mental health experts say coaches can learn to practice reflective listening, hold space for athletes to talk, and then process the information and determine next steps if they hear certain comments from their athletes.

2

Unpaid coaches feel less confident than paid coaches in many areas. The youth sports system in the U.S. relies on volunteer coaches. They’re often trying their best, including taking trainings without being paid. Without these volunteers, not enough coaches would be available. Yet unpaid coaches expressed significantly less confidence than paid coaches in many areas, such as helping athletes succeed academically, setting clear expectations for how the coach chooses a team, coaching players’ skills on the field, maximizing team strengths during games, assessing physical conditioning of athletes, and identifying mental health challenges.

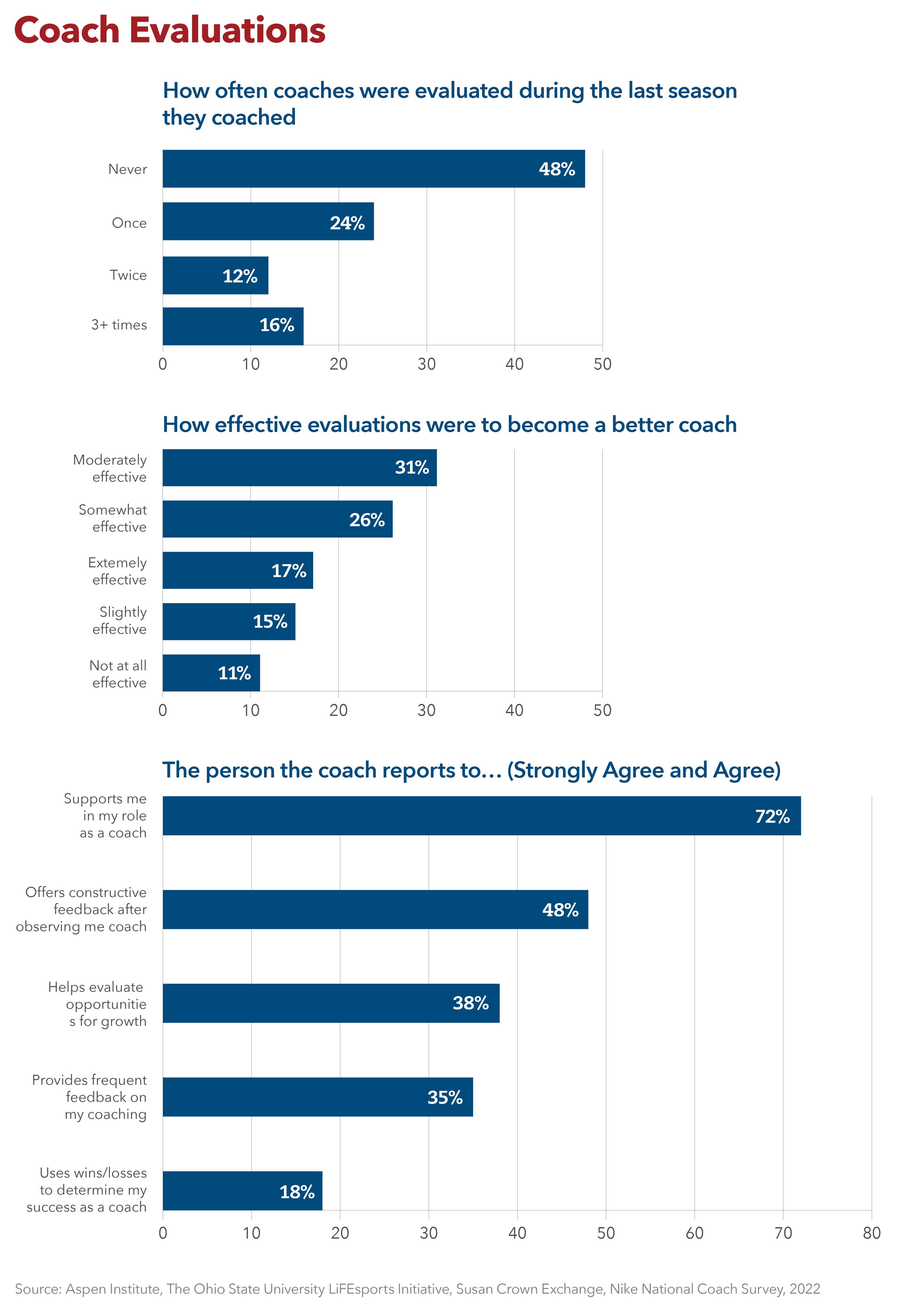

Unpaid coaches (45%) were far more likely than paid coaches (19%) to never be evaluated. Nearly half of all surveyed coaches (48%) said they were never evaluated in the last season they coached. Of those who had been evaluated, approximately half said their evaluations were moderately or extremely effective in helping them be a better coach. Meanwhile, 1 in 4 said evaluations were slightly or not at all effective. Coaches without a coaching certification or license (54%) were more likely to never be evaluated than certified/licensed coaches (44%).

The majority of coaches (72%) said the person they report to generally supports them. However, feelings about the nature of that support were mixed. Less than half of coaches agreed that their supervisor offered constructive and frequent feedback and helped evaluate opportunities for growth.

3

Parents trust coaches and expect a lot from them; coaches get frustrated by parents. In general, coaches are satisfied with their coaching experiences (96% reported feeling moderately, very or extremely satisfied) and are fairly likely to continue coaching (95% reported feeling somewhat or extremely likely to continue coaching), according to the National Coach Survey. But 69% of coaches also reported feeling moderately, very or extremely stressed. Coaches were rarely positive in their perspectives of parent behaviors in sports settings. For instance, two-thirds of coaches reported parents sometimes, often or always criticize the performance of their own child and the performance of game officials. Half of the coaches reported that parents criticize their child’s teammates or opposing players, and one-third report parents criticize their coaching. Only about 6 in 10 coaches said parents often or always model good sportspersonship with opposing parents. Recreational coaches reported more positive parent behaviors than club and school coaches.

Meanwhile, in a separate survey, youth sports parents expressed more trust in their child’s coach than national, state and community leaders, and their child’s school, teachers and peers to develop life skills, foster a sense of belonging, create safe environments to play, help youth identify and cope with off-the-field stressors, and earn the child a college scholarship. The findings raise questions: Can coaches be all things to all people? How can parents and coaches better communicate what each of them value – and then put those stated values into practice?

Most coaches in the National Coach Survey said they are motivated by a love of teaching sport and wanting to develop young people in their communities. They said developing young people was influential in their decision to become a coach. Roughly 3 in 4 coaches played a sport as a child. And although coaches were seven times more likely to be extremely satisfied than extremely stressed, 6 in 10 coaches expressed interest in more stress management training. Coaches would welcome more help.

4

Men are twice as likely to coach the opposite gender as women. In the National Youth Coach survey, 17% of men reported coaching female teams most often compared to 8% of women who coach male teams most frequently. This speaks to cultural factors and biases associated with women coaching males at all levels of sports – adding to the challenge of recruiting more female coaches. Both the National Coach Survey and Sports & Fitness Industry Association data showed that about three-quarters of youth sports coaches are men.

In the National Coach Survey, 67% of male coaches said they were extremely likely to continue coaching vs. 60% of female coaches. The survey showed a higher rate of inexperienced coaches who are female – 36% of women had coached one to five years vs. 27% of men. Male coaches (48%) reported having coached more than 10 years as compared to women respondents (39%).

Men and women reported nearly equal rates of frustration related to not having enough peer and administration support, as well as a desire for more pay. Both men and women reported equal rates (12%) among those paid $10,000 or more to coach in their last season. More women (44%) than men (32%) served as paid coaches making $5,000 or less.

91%

Percentage of coaches trained in youth development who reported having an impact on their athletes becoming models in their communities vs. 77% of untrained coaches.

Coach training matters. The National Coach Survey demonstrates that coaches who participated in trainings focused on sport skills and tactics and youth development were significantly more confident in their coaching behaviors than those who had not. Findings were particularly strong for coaches trained in youth development strategies such as developing leaders, teaching life skills, and supporting mental health.

5

Educators are disappearing as school-based coaches. For generations of students, school sports usually meant being coached by an educator working in the same building or another local school. Today, only 50% of school-based coaches are teachers or educators, according to the National Coach Survey. The remaining school coaches largely identified as coming from other professions (18%, most commonly in the business arena), being a parent of an athlete (15%) or being a volunteer (12%). This means many school coaches lack background around learning and youth development that a teacher may receive. Coaches employed in the school are more confident (47% to 33%) in their ability to ensure their athletes succeed academically. That makes sense since these coaches tend to be more connected to students’ academic situations, including proximity to teachers and grades.

81%

Percentage of coaches who say there is a need for more coaches in their community, according to the National Coach Survey. The shortage of coaches impacts how many teams can be formed.

However, one key finding is that coaches who are educators feel about as confident teaching certain interpersonal skills as coaches who are non-educators. For instance, here are the rates of coaches expressing strong confidence in: teaching life skills through sport (52% educators vs. 45% non-educators), resolving interpersonal conflicts on a team (34% vs. 30%), using goal-setting techniques with athletes (33% vs. 36%), and helping athletes regulate emotions (27% vs. 24%). In other words, many coaches need support in areas some might assume educators would automatically thrive.

Among all coaches, a majority said they lack preparedness for working with young people experiencing disabilities and/or disorders. Eating disorders (only 36% felt moderately or extremely prepared), intellectual or developmental disabilities (45%) and physical disabilities (46%) were among the issues coaches don’t feel prepared addressing.

"Fewer and fewer coaches have backgrounds in education and child development. Many teachers are choosing not to coach, and community-based coaches feel far less prepared than those working in schools. What this means is most coaches today have limited skills in teaching sport skills and tactics, as well as in supporting kids' mental health and development."

— Dawn Anderson-Butcher, Professor and Co-Executive Director, LiFEsports

Read all State of Play 2022 coaching charts here.

Research Sources

National Coach Survey – The Ohio State University LiFEsports Initiative, Aspen Institute, Susan Crown Exchange, Nike

Sports & Fitness Industry Association (SFIA)

National Youth Sports Parent Survey – Aspen Institute, Utah State University, Louisiana Tech University, TeamSnap